There’s a curious thing that happens when I travel with my eyes open. I begin to notice not just what is present in a place, but what is absent. I start to see the spaces—the voids that speak in ways words cannot. And more interestingly, I begin to observe how these absences are interpreted, not just by the inhabitants, but by the culture itself. What is missing tells me something about what is valued, what is discarded, and perhaps what is taken for granted.

I’ve been fortunate (or perhaps restless) enough to cross a few borders in my life—both literal and philosophical. What I’ve found is that minimalism, that slippery, overused term, is neither universal nor consistent. It shapeshifts. It adapts to context, responding to cultural, spiritual, and economic imperatives. And more often than not, it reveals more about a culture’s interior life than its surface ever could.

Minimalism, it turns out, isn’t just a Western export stamped in Helvetica and marketed through YouTube vlogs. Its roots are far older, deeper, and more varied than the sleek, modernist ideals it has come to represent in the global imagination. In the quieter corners of the world, minimalism isn’t just an aesthetic choice; it is a rhythm, a ritual, a way of understanding one’s place in the world. It speaks to a desire not to escape the world, but to engage with it more meaningfully—with less distraction and more clarity.

The question, then, is not if people live minimally, but why, how, and to what end. In this exploration of minimalism’s global manifestations, we discover that what’s considered “essential” and “superfluous” varies as widely as the landscapes, histories, and philosophies that inform them. And perhaps, in reflecting on how others have embraced—or resisted—minimalism, we may come to understand more clearly how we, too, might choose to live.

Japan and the subtle power of absence

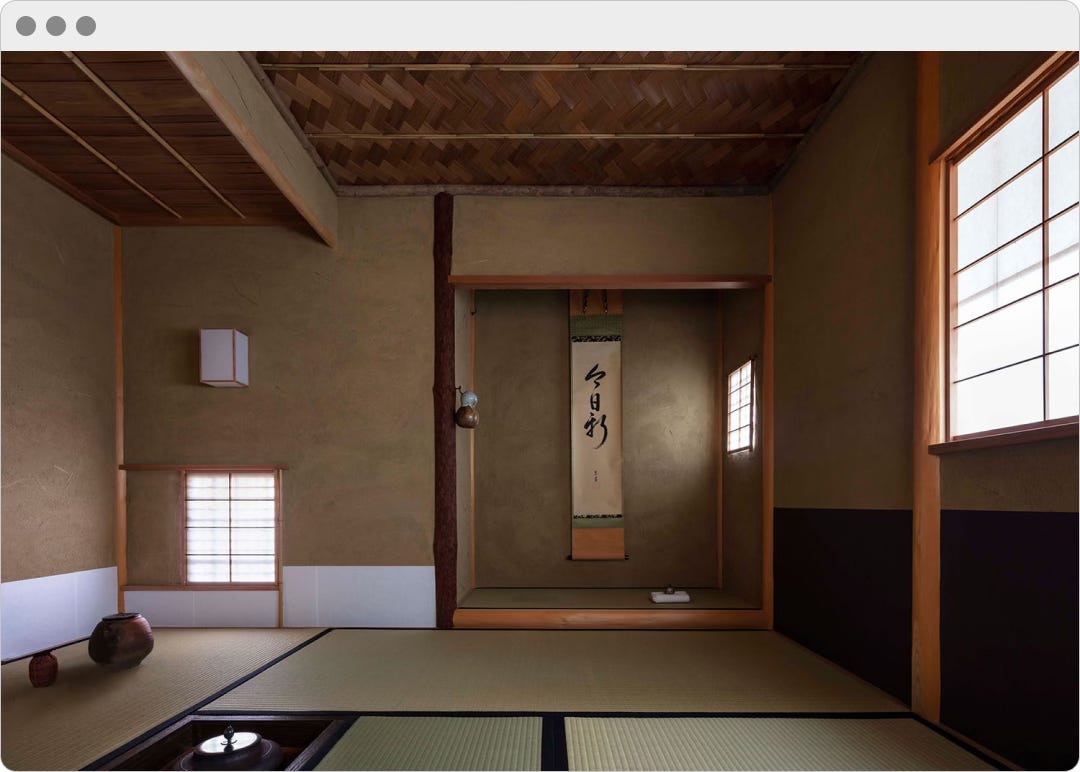

In Japan, minimalism is a way of life rather than merely an aesthetic or philosophical pursuit. A deeply ingrained principle in Japanese culture, minimalism speaks to an intimate connection with nature and the spiritual world. It’s not just about reducing clutter; it’s about creating space for something more profound: ma, or the empty spaces between objects and moments. In the practice of Zen, ma is a silence that speaks louder than any physical presence. It is not the absence of things, but the presence of possibility.

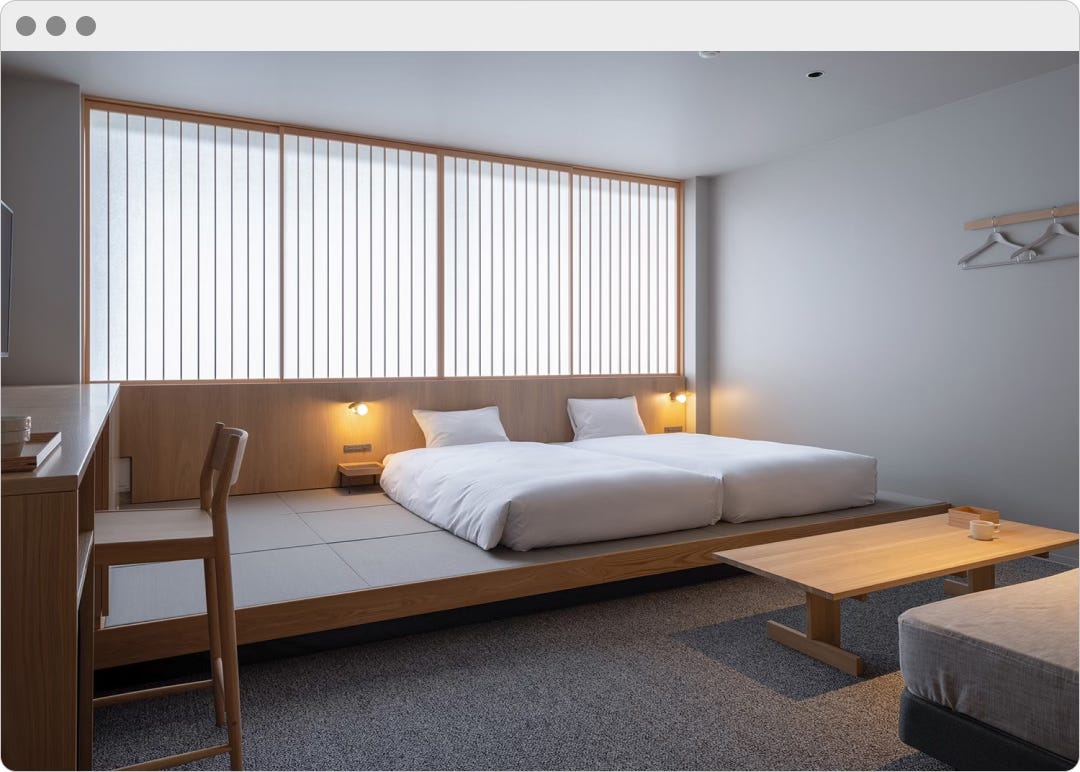

Traditional Japanese homes are designed with minimal ornamentation, yet the simplicity in their design evokes a sense of beauty and serenity that is unmatched in the contemporary world. Each item in the home—whether a low wooden table or a simple shoji screen—serves a functional and aesthetic purpose. The home is a space not just for living, but for contemplation. The clean lines and empty spaces are symbolic of a life lived with intention, where each element, even in its simplicity, is given room to breathe.

This isn’t merely an aesthetic choice—it’s rooted in centuries of spiritual practice. Japanese gardens, for example, may seem barren at first glance, but in their simplicity lies a world of meaning. Every stone, every raked line of gravel, invites reflection and mindfulness. To the untrained eye, there may be nothing; to those who look closely, there is everything. It is an invitation to engage in the world with presence and awareness—to embrace the silence and find richness in what is not immediately visible.

As the Zen Buddhist master Dogen once said, “To live in the moment is to live as though the world is already complete.” In this, minimalism is not about stripping life of its richness, but about making space for its quiet magnificence.